Synopsis:

The following synopsis has been culled from notes of the symposium sessions. It is offered here to provide some sense of the symposium’s topics and discussions, especially for those who could not attend but may wish to participate in the future. These summaries of participants’ comments are not verbatim nor are they complete, and may not be used for citation. For further information about the topics mentioned here, refer first to the participants’ published works (see the Iconic Books Bibliography) and then contact the individual participants themselves.

Friday, September 4th:

Scholars working in different disciplines and specializing in different cultures and time periods gathered to share data and insights on iconic books and texts. Brent Plate (Hamilton) opened the symposium and introduced Dean Joseph Urgo who welcomed the assembled scholars to Hamilton College.

Jim Watts (Syracuse University) gave the opening address. He reviewed the nine-year history of the Iconic Books Project that set the stage of this series of symposia. The goal is to create a new academic discourse around this subject. The last symposium put six significant issues on the table that participants this year might want to take up.

- Is the terminology of “icon” and “iconic” appropriate for texts from unrelated cultures and time periods? What alternative terms are available? Dori Parmenter has defined “iconic book” as functionally identical to icons as understood by Eastern Orthodox theologians.

- The problem of comparison: Comparisons between superficially similar phenomena in separate cultures and periods suffer from lack of control, as is widely recognized. How can comparison of iconic book practices avoid this well-known pitfall? Watts noted that comparative study casts the materials of his own specialty in a different light and, for him, that is its principal value.

- The distinction between religious and secular texts: Is there anything distinctive about the iconicity of religious texts?

- The functional relationship between iconicity and the other dimensions of texts: How do practices of visual display and material manipulation influence the reading and interpretation of particular text? Watts reviewed briefly his own theory of the three dimensions (semantic, performative, iconic) of texts, then invited critique and alternative proposals.

- The socio-political location of iconic book practices: Books and other texts mediate social power both within communities and between them. They do so iconically as well as semantically, though with different effects.

- Value-judgments about iconic book practices: The usual attitude of scholars towards iconic book and text practices is disparaging and dismissive. Not only do such judgments interfere with analyzing the phenomenon, but these old preconceptions also need to be studied and understood in social context.

Watts proceeded to apply some observations from the first symposium to materials in his own field. Surviving texts from the ancient Near East exhibit four kinds of iconicity: (1) tablets and scrolls serve as marks of status and expertise in portraits of scribes; (2) monumental texts demonstrate royal and temple power and wealth; (3) kings and priests displayed old texts to legitimize ritual performances; (4) myths describe heavenly texts in which the gods write human fates. This last category includes Mesopotamian stories of battles among the gods to possess such “Tablets of Destiny” and thereby become king of the gods. These myths reflect the politics of textual production and possession in many ancient Near Eastern courts. The Assyrian king, Assurbanipal, built his massive library through conquest and used it as an instrument of oversight and control. The myths reflect the fact that possession of iconic texts conveys cultural prestige and political supremacy.

Saturday, September 5th:

The symposium proceeded on the following days with discussion sessions introduced by presentations by each of the panellists.

9:00: Brent Plate (Hamilton College) pointed out that written words are images. He illustrated this point by noting how the shape of handwritten script or printed typefaces has been used in advertising, in Qur’anic manuscripts and in graffiti. Page layout also influences how readers receive the image of the text. Qur’anic pages frequently have borders that frame them and Bibles are conventionally laid out in two columns. Explicit agendas often determine choices of font and layout: the Protestants’ emphasis on clarity and communication stimulated the creation of more readable fonts (e.g. Baskerville) which has been continued by advertisers who design for communicative transparency (e.g. Helvetica). Plate concluded that “words are images,” thus interpretation is also emotional and affective. As a result the three dimensions of texts (semantic, performative and iconic) cannot be separated. All three always influence readers. 9:00: Brent Plate (Hamilton College) pointed out that written words are images. He illustrated this point by noting how the shape of handwritten script or printed typefaces has been used in advertising, in Qur’anic manuscripts and in graffiti. Page layout also influences how readers receive the image of the text. Qur’anic pages frequently have borders that frame them and Bibles are conventionally laid out in two columns. Explicit agendas often determine choices of font and layout: the Protestants’ emphasis on clarity and communication stimulated the creation of more readable fonts (e.g. Baskerville) which has been continued by advertisers who design for communicative transparency (e.g. Helvetica). Plate concluded that “words are images,” thus interpretation is also emotional and affective. As a result the three dimensions of texts (semantic, performative and iconic) cannot be separated. All three always influence readers.

Dan Moseson (Syracuse) observed that differences in script and font are the visual equivalent of differences in tone and inflection in speech. Zeev Elitzur (Ben-Gurion) remarked that we should distinguish between iconic “texts” by virtue of their script or font and iconic “books” by virtue of their physical form.

9:45: Timothy Beal (Chase Western Reserve) asked, “Is the medium the icon?” He distinguished between the cultural iconicity of the idea of the Bible and particular iconic Bibles, and wondered how the idea of the Bible can contain such a variety of different forms of Bibles, ranging from traditional, leather-bound codices to children’s bibles, Bibles in magazine format (“biblezines”), and graphic novel format. Furthermore, the word “bible” gets used in to describe any kind of authoritative handbook with connotations of accessibility, comprehensiveness and exclusiveness. Beal argued that the combination of tech culture with marketing capitalism is deconstructing the Bible as iconic book. He distinguished between the cultural iconicity of the idea of the Bible and particular iconic Bibles, and wondered how the idea of the Bible can contain such a variety of different forms of Bibles, ranging from traditional, leather-bound codices to children’s bibles, Bibles in magazine format (“biblezines”), and graphic novel format. Furthermore, the word “bible” gets used in to describe any kind of authoritative handbook with connotations of accessibility, comprehensiveness and exclusiveness. Beal argued that the combination of tech culture with marketing capitalism is deconstructing the Bible as iconic book.  Believing that the message (“the Word”) transcends any and every medium, evangelical publishers feel free to transform the Bible continuously. But Beal also noted that the Bible has never been as unified and singular as popular notions of it suggest. There have always been a plurality of Bibles and forms of Bibles. He wondered if, in fact, as a “cultural icon” the idea of the Bible gains its power from its amorphous boundaries. Believing that the message (“the Word”) transcends any and every medium, evangelical publishers feel free to transform the Bible continuously. But Beal also noted that the Bible has never been as unified and singular as popular notions of it suggest. There have always been a plurality of Bibles and forms of Bibles. He wondered if, in fact, as a “cultural icon” the idea of the Bible gains its power from its amorphous boundaries.

Kristina Myrvold (Lund) pointed out that traditions usually exist in tension between efforts to establish eternal and unchanging practices and beliefs on the one hand, and the constant need to re-perform and recontextualize them on them other, as anthropologists have long observed.

10:30: Tazim Kassam (Syracuse) worried that “iconic” is a scholars' label with which participants in Muslim worship would not identify. The Qur’an, in book form, plays little role in either worship or art. Instead, it is performed orally, best from memory, and its visual impact comes from its verses inscribed on mosques and elsewhere. In contrast to the Bible as described by Beal, the Qur’an is not pluriform, but singular: one text, one language. Even the Qur’anic pages that frame the text with elaborate borders described by Plate also include elements that point off the page to indicate that scripture cannot be contained by the page. It is “a book that resists being a book” and is therefore in an important sense aniconic. Only in modern times have Qur’ans begun to play iconic roles when portrayed on monuments or held high during protest demonstrations. 10:30: Tazim Kassam (Syracuse) worried that “iconic” is a scholars' label with which participants in Muslim worship would not identify. The Qur’an, in book form, plays little role in either worship or art. Instead, it is performed orally, best from memory, and its visual impact comes from its verses inscribed on mosques and elsewhere. In contrast to the Bible as described by Beal, the Qur’an is not pluriform, but singular: one text, one language. Even the Qur’anic pages that frame the text with elaborate borders described by Plate also include elements that point off the page to indicate that scripture cannot be contained by the page. It is “a book that resists being a book” and is therefore in an important sense aniconic. Only in modern times have Qur’ans begun to play iconic roles when portrayed on monuments or held high during protest demonstrations.

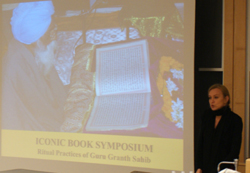

11:00: Gurinder Singh Mann (U.C. Santa Barbara) reviewed the manuscript history of the Sikh scriptures, Guru Granth Sahib. Fully canonized in the early 1700s, manuscripts of older precursors now serve as relic texts, cherished and preserved but not ritually recited and interpreted. The Sikh community shows great interest in the Guru Granth’s mode of production and its two original scribes who are often depicted in Sikh iconography. The ritual treatment of the text has remained basically the same over three centuries, though details vary. The founding gurus served as the medium for the text and were subservient to the transmission of the text; once it was complete, it replaced the gurus. Therefore, Mann argued that Guru Granth is not primarily a visual symbol but personal—that which is prayed to and which answers through its text. The exchange is not primarily visual, as in Hindu practice, but rather aural in nature. 11:00: Gurinder Singh Mann (U.C. Santa Barbara) reviewed the manuscript history of the Sikh scriptures, Guru Granth Sahib. Fully canonized in the early 1700s, manuscripts of older precursors now serve as relic texts, cherished and preserved but not ritually recited and interpreted. The Sikh community shows great interest in the Guru Granth’s mode of production and its two original scribes who are often depicted in Sikh iconography. The ritual treatment of the text has remained basically the same over three centuries, though details vary. The founding gurus served as the medium for the text and were subservient to the transmission of the text; once it was complete, it replaced the gurus. Therefore, Mann argued that Guru Granth is not primarily a visual symbol but personal—that which is prayed to and which answers through its text. The exchange is not primarily visual, as in Hindu practice, but rather aural in nature.

11:30: Kristina Myrvold (Lund) described four types of text ritual among contemporary Sikh communities: (1) rituals of recitation, transmission and interpretation; (2) using recitation to accomplish specific results, e.g. to create nectars for healing; (3) rituals in which the scripture plays a central role in social life, e.g. weddings; (4) veneration of scripture as the living guru. After giving examples and drawing further distinctions within these various categories, she drew attention especially to “life-cycle” rituals in which the creation, preservation and disposal of the Guru Granth are ritualized on analogy with the rituals that mark human life transitions. Identified as the “living Guru” with whom Sikh worshipers stand in relationship, the scripture functions for Sikhs less iconically than indexically, i.e. as a marker of identity. 11:30: Kristina Myrvold (Lund) described four types of text ritual among contemporary Sikh communities: (1) rituals of recitation, transmission and interpretation; (2) using recitation to accomplish specific results, e.g. to create nectars for healing; (3) rituals in which the scripture plays a central role in social life, e.g. weddings; (4) veneration of scripture as the living guru. After giving examples and drawing further distinctions within these various categories, she drew attention especially to “life-cycle” rituals in which the creation, preservation and disposal of the Guru Granth are ritualized on analogy with the rituals that mark human life transitions. Identified as the “living Guru” with whom Sikh worshipers stand in relationship, the scripture functions for Sikhs less iconically than indexically, i.e. as a marker of identity.

Joanne Waghorne suggested that this exemplifies also the function of human gurus in Indic traditions as mediating between iconicity and semantic teaching, between the ruler (maharajah) and the ascetic. Mann responded that Sikhs, however, distinguish sharply between the Guru Granth and God, just as they clearly distinguish the historical human gurus from God.

12:15: Jim Watts related an anecdote about a Sikh man who, when asked if he had a copy of Guru Granth in his home, responded “No, that book is entirely too much trouble.” He contrasted that with typical Christians who often own many copies of the Bible. But the two traditions both ritualize their scriptures to a high degree, just in opposite ways. Christians accumulation of multiple Bibles indicates ritual veneration as well. Watts also argued that so-called “modern” attitudes towards translatability and mutability of textual contents may reflect the culture’s religious presuppositions, since Christians since antiquity have tended to take this attitude towards the Bible, as Beal already illustrated.

2:00: Lisa Gitelman (NYU) described her research interest in “the social life of paper,” more broadly, “how the instruments and practices of knowledge production work to construct the practices by which knowledge is defined.” Echoing Watts’ observation that a realistic picture of a text is a text, she wondered what other kinds of pictorial subjects are equivalent to their own image. Gitelman presented two books as examples: a 19th century volume that reproduces examples of job printing (receipts, playbills, invitations, etc.) and a 21st century art book that reinscribes the entire New York Times for September 1, 2000, in book (novel) format. She asked if such books make ephemera iconic. Is ephemerality the opposite of iconicity? 2:00: Lisa Gitelman (NYU) described her research interest in “the social life of paper,” more broadly, “how the instruments and practices of knowledge production work to construct the practices by which knowledge is defined.” Echoing Watts’ observation that a realistic picture of a text is a text, she wondered what other kinds of pictorial subjects are equivalent to their own image. Gitelman presented two books as examples: a 19th century volume that reproduces examples of job printing (receipts, playbills, invitations, etc.) and a 21st century art book that reinscribes the entire New York Times for September 1, 2000, in book (novel) format. She asked if such books make ephemera iconic. Is ephemerality the opposite of iconicity?

The ensuing discussion noted that collector’s use of the very category of “ephemera” changes the status of such items into something worth collecting and so no longer ephemeral at all.

2:45: Patrick Graham (Emory) described the Digital Image Archive of Pitts  Theological Library at Emory University, which contains an especially large collection of Reformation-era woodcuts and prints. Searching for “book” in the Archive produced 800 results, “scroll” 150 more. The results fall into several different categories: books and scrolls appear as (1) representations of actual liturgical scenes from the time of the artists; (2) attributes in portraiture; (3) weapons of polemical satire; and (4) title-page borders. Graham noted that illustrated texts tend to be read in light of the illustrations, because the pictures draw attention first. Theological Library at Emory University, which contains an especially large collection of Reformation-era woodcuts and prints. Searching for “book” in the Archive produced 800 results, “scroll” 150 more. The results fall into several different categories: books and scrolls appear as (1) representations of actual liturgical scenes from the time of the artists; (2) attributes in portraiture; (3) weapons of polemical satire; and (4) title-page borders. Graham noted that illustrated texts tend to be read in light of the illustrations, because the pictures draw attention first.

3:30: Phil Arnold (Syracuse) gave two examples of the impact of conquest and  colonialism on book culture. (1) Because of a traumatic history with book-oriented cultures, many indigenous people now exhibit attitudes that are anti-Bible, anti-book and, often, anti-text-based education. (2) Aztecs produced native papers that were used in power relationships within their own culture. Collected and catalogued by anthropologists, those same papers become tools for power relationships in Western academic culture. colonialism on book culture. (1) Because of a traumatic history with book-oriented cultures, many indigenous people now exhibit attitudes that are anti-Bible, anti-book and, often, anti-text-based education. (2) Aztecs produced native papers that were used in power relationships within their own culture. Collected and catalogued by anthropologists, those same papers become tools for power relationships in Western academic culture.

4:00: Zeev Elitzur (Ben-Gurion) argued that a major transition in the scriptural function of Torah occurred in Judaism between the second and fourth centuries C.E. Only in Talmudic texts from the later period were scriptures limited to the Hebrew language alone. It was then that interpretation increasingly focused on visual aspects of the Hebrew text, such as letter forms and spellings. Earlier sources (Mishnah and related literature) obscure the story of Moses receiving scrolls of Torah at Mt. Sinai, while later (Talmudic) ones emphasize it. Elitzur suggested that this development was due, in large part, to developing ideas of the “oral torah” in the later period. The elevated statue of the oral torah enhanced by contrast the significance of the material form of written torah, emphasizing the sign more than what it signifies. 4:00: Zeev Elitzur (Ben-Gurion) argued that a major transition in the scriptural function of Torah occurred in Judaism between the second and fourth centuries C.E. Only in Talmudic texts from the later period were scriptures limited to the Hebrew language alone. It was then that interpretation increasingly focused on visual aspects of the Hebrew text, such as letter forms and spellings. Earlier sources (Mishnah and related literature) obscure the story of Moses receiving scrolls of Torah at Mt. Sinai, while later (Talmudic) ones emphasize it. Elitzur suggested that this development was due, in large part, to developing ideas of the “oral torah” in the later period. The elevated statue of the oral torah enhanced by contrast the significance of the material form of written torah, emphasizing the sign more than what it signifies.

4:30: Jason Larson (Syracuse) defined an iconic book as “a great gift book.”  Recalling his own experience as an archivist with the ideologies of archive management, he pointed out the importance of inscriptions as sites of politicized memory in the ancient Roman empire. By contrast, early Christians developed sites of memory in relics and Gospel books which had the advantage of being portable. When Emperor Diocletion attacked Christian books to suppress the movement, many people cut off the iconic Christian bindings and stuffed them with other contents before giving them to the Romans. The consequence of such persecution was to elevate books as sites of memory to a status equal to bodily relics. That status was confirmed by Constantine’s official publication of Christian books as a sign of its new status in the empire. Recalling his own experience as an archivist with the ideologies of archive management, he pointed out the importance of inscriptions as sites of politicized memory in the ancient Roman empire. By contrast, early Christians developed sites of memory in relics and Gospel books which had the advantage of being portable. When Emperor Diocletion attacked Christian books to suppress the movement, many people cut off the iconic Christian bindings and stuffed them with other contents before giving them to the Romans. The consequence of such persecution was to elevate books as sites of memory to a status equal to bodily relics. That status was confirmed by Constantine’s official publication of Christian books as a sign of its new status in the empire.

5:15: Dori Parmenter (Spalding) pointed out that Eastern Orthodox Christianity emphasizes not just the visual aspect, but also the material nature of icons. They are material mediators of the unseen world. She therefore echoed Elitzur in distinguishing icon (= books as art, material objects, manipulated in book rituals) from iconicity (= books in art, visual objects, symbols). She also emphasized that Orthodox icons derive their significance from both ritual and myth. The Bible and many other scriptures do as well.

Sunday, September 6th:

9:00: Yohan Yoo (Seoul National U.) recalled Mircea Eliade’s observation that elite social groups regard sacred things as symbolic, but lay people think of them as the sacred itself. He reviewed academic studies of scripturality to show that lay practices and beliefs have been ignored. In Korean Buddhism, monks monopolize the performative and interpretive dimensions of Buddhist scriptures, but they support the iconic rituals of the laity. Koreans and Japanese use Buddhist scriptures written in classical Chinese. Translations into Korean, though available since the 15th century, have received little use until recently. However, the Buddhist canon was published on a monumental scale from the 11th century on to guarantee military protection for the country. A sutra was given royal parades to drive away disasters and diseases from the capital of Koryo dynasty. Rotating prayer turrets and walking sutra mazes allow lay people to “pray” the sutras through physical activity. Technological changes have recently contributed to a democratization of sutra recitation and writing. Major temples produce CDs and internet sites that make recitations readily available. Some sites even allow people to write a sutra verse on their own computer. Like many other kinds of sutra merchandise, they are marketed as providing positive karma and avoid misfortunate. 9:00: Yohan Yoo (Seoul National U.) recalled Mircea Eliade’s observation that elite social groups regard sacred things as symbolic, but lay people think of them as the sacred itself. He reviewed academic studies of scripturality to show that lay practices and beliefs have been ignored. In Korean Buddhism, monks monopolize the performative and interpretive dimensions of Buddhist scriptures, but they support the iconic rituals of the laity. Koreans and Japanese use Buddhist scriptures written in classical Chinese. Translations into Korean, though available since the 15th century, have received little use until recently. However, the Buddhist canon was published on a monumental scale from the 11th century on to guarantee military protection for the country. A sutra was given royal parades to drive away disasters and diseases from the capital of Koryo dynasty. Rotating prayer turrets and walking sutra mazes allow lay people to “pray” the sutras through physical activity. Technological changes have recently contributed to a democratization of sutra recitation and writing. Major temples produce CDs and internet sites that make recitations readily available. Some sites even allow people to write a sutra verse on their own computer. Like many other kinds of sutra merchandise, they are marketed as providing positive karma and avoid misfortunate.

9:45: Joanne Waghorne (Syracuse) reported her observation in Singapore of a “Gita Jayanti,” a birthday party for the Bhagavad Gita. The celebrations included party invitations, ritualization of the Gita’s semantic dimension through scholarly panels and lay quizzes, the performative dimension in a chanting competition for boys and girls, and the iconic dimension through the havan—fire pit ceremonies for each chapter. Here in Singapore this ancient Vedic ritual has been popularized and made inclusive of women, children and people of many backgrounds. (The Gita is short and didactic and has therefore was singled out to function as “Hindu scripture” by British colonialists in India. Now in the Hindu diaspora, people will take legal oaths on the Gita on analogy with the Christian Bible.) In the havan, the Gita’s words are recited over the fire to transform them so that their essence accumulates in water that is then poured on the image of Krishna—thus returning the divine words to the god who spoke them. Thus the words of the Gita become incorporated by a literal icon. Afterwards, worshipers drink the water, thus imbibing the words into their bodies. 9:45: Joanne Waghorne (Syracuse) reported her observation in Singapore of a “Gita Jayanti,” a birthday party for the Bhagavad Gita. The celebrations included party invitations, ritualization of the Gita’s semantic dimension through scholarly panels and lay quizzes, the performative dimension in a chanting competition for boys and girls, and the iconic dimension through the havan—fire pit ceremonies for each chapter. Here in Singapore this ancient Vedic ritual has been popularized and made inclusive of women, children and people of many backgrounds. (The Gita is short and didactic and has therefore was singled out to function as “Hindu scripture” by British colonialists in India. Now in the Hindu diaspora, people will take legal oaths on the Gita on analogy with the Christian Bible.) In the havan, the Gita’s words are recited over the fire to transform them so that their essence accumulates in water that is then poured on the image of Krishna—thus returning the divine words to the god who spoke them. Thus the words of the Gita become incorporated by a literal icon. Afterwards, worshipers drink the water, thus imbibing the words into their bodies.

The following discussion noted how the political and social context of Singapore has been imprinted on the ritual, including sponsorship by a government official, the requirement of open access to temples, etc.

10:30: Dori Parmenter (Spalding) showed pictures of a billboard of the Ten Commandments beside a highway in Ohio to prompt a lively discussion of how its distinctive text fonts and lack of labelling prompted diverse responses from different kinds of people.

11:00: The concluding roundtable discussion ranged across issues of terminology (icon, iconicity, relic, and textual practices that fall somewhere in between), the socio-political location of iconic book practices (lay vs. elite, the effects of politics, colonization, modernization and globalization) and the role of value judgments in their analysis (how theological assumptions bias assessment vs. the importance of paying attention to emic descriptions of how books and scriptures function). Additional issues that should factor into analysis of iconic books include (1) how texts can function as or in place of persons, and (2) how digital texts are being ritualized.

Postscript: A third symposium on iconic books will take place in October 1-3, 2010, at Syracuse University. On this occasion, participants will be asked for written papers which can be pre-circulated and discussed at the symposium. Details will be posted to this website soon.

(Thanks to Cordell Waldron for taking the pictures!) |